Harnessing K-way Merge Sorted Sets for Top Product Selection in E-Commerce Platforms

Hello, fellow keyboard warriors and screen heroes of the tech world! 🌍

Problem: The Category Conundrum

So, here's the deal. My organization sells everything ranging from grocery to fashion, we have it all. On our platform, we have these lovely widgets that show products classified into different category labels namely super_category ,primary_category, sub_category, and product_types. This problem is more focused on the home page widgets, but the same was implemented to other pages like search and category-specific pages as well, skipping that for now otherwise this blog becomes too lengthy.

Before going further let me first talk about the architecture of our app's home page. It has a hierarchical tree structure with the homepage (or root) spawning multiple child Widgets, we call them CMS Items (which themselves can be parents to their own children CMS items). To help visualize and communicate this more clearly to you, I'll provide an illustrative breakdown of the structure:

- HomePage (Root CMS Item)

|

├── Previously Bought (Child CMS Item of HomePage which is a SKU List)

|

├── De Dana Dan Sale (Child CMS Item of HomePage)

| |

| ├── Women's Fashion (Child CMS Item of De Dana Dan Sale)

| |

| ├── Men's Fashion (Child CMS Item of De Dana Dan Sale)

| | |

| | ├── Jeans & Trousers (Child CMS Item of Men's Fashion)

| | |

| | ├── Wallets & Watches (Child CMS Item of Men's Fashion)

| | |

| | ├── Kurtas (Child CMS Item of Men's Fashion)

| | |

| | └── SKU List (Child CMS Item of Men's Fashion)

| |

| └── Shoes & Slippers (Child CMS Item of De Dana Dan Sale)

|

└── Recently Viewed (Child CMS Item of HomePage which is a SKU List)

This tree-like structure allows for a scalable and organized architecture. Any component (or CMS item) can be easily located by navigating through its parent-child relationships. As users navigate through the app, they are essentially traversing this tree structure from one CMS item to another. This design provides a strong foundation for building a dynamic and user-friendly app experience.

Furthermore, each CMS item of the SKU list type houses a collection of products. These products link to a marketing category potentially spanning the four main categories. The challenge? Showcasing products based on popularity, ensuring the ads align with the widget's categories. To tackle this, we mapped the cmsItemId to the three main categories, omitting super_category to yield more targeted ads.

Now, the management, in their infinite wisdom, decided that we should show ads for products that were blockbuster hits last month. So, let's say we have X slots for ads in a widget, which could have Y types of categories. Each category can have Z different kinds of products. Yep, it's XYZ, and we're not talking algebra, people!

Two Roads Diverged in a Widget Wood...

Here are two strategies we were considering, Let's break down the time complexity for both approaches:

1. The Lazy Approach:

Here are the primary steps involved in this approach:

a. Merge Products: Merging all the products would take time proportional to the total number of products. If Z is the average number of products in each of the Y categories, then the total number of products are ( Y times Z ). Thus, the time complexity of this step is ( O(YZ) ).

b. Sort Based on Popularity: Sorting ( Y times Z ) items using a comparison sort (like mergesort or quicksort) would have a time complexity of ( O(YZ log(YZ)) ).

c. Pick Top X: Selecting the top X from the sorted list is ( O(X) ), which in the worst case (when ( X = YZ )) is ( O(YZ) ). However, in practice, ( X ) is likely to be much smaller than ( YZ ), so this operation is generally quite fast.

Overall time complexity for the Lazy Approach: ( O(YZ log(YZ)) )

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sort"

)

// Product represents an individual product with a unique SKU and an associated Score.

type Product struct {

SKU string

Score int64

}

// mergeAndSortProducts merges multiple slices of products into one, sorts them based on their scores in descending order,

// and returns the top x products.

func mergeAndSortProducts(productSlices [][]Product, x int) []Product {

// Create an empty slice to store all products from the given product slices.

mergedProducts := make([]Product, 0)

// Loop through each product slice and append its products to the mergedProducts slice.

for _, products := range productSlices {

mergedProducts = append(mergedProducts, products...)

}

// Sort the mergedProducts slice in descending order of Score.

sort.Slice(mergedProducts, func(i, j int) bool {

return mergedProducts[i].Score > mergedProducts[j].Score

})

// If x exceeds the number of products in mergedProducts, adjust x to the length of mergedProducts.

if x > len(mergedProducts) {

x = len(mergedProducts)

}

// Return the top x products.

return mergedProducts[:x]

}

2. The Techie Approach:

For this approach:

a. Maintain a Sorted Set for Each Category: The complexity of inserting an item into a sorted set is ( O(log Z) ) for balanced binary search trees or skip lists (commonly used data structures for sorted sets). If you're doing this for ( Z ) products in each of the ( Y ) categories, the total complexity is ( O(YZ log Z) ).

b. Use Iterators: This is a bit tricky. When selecting the top-scoring products, you're essentially merging ( Y ) sorted sets. The complexity of this operation, in the worst case, is proportional to ( X times Y ) because, for each of the ( X ) products you select, you might have to look at all ( Y ) categories (in the worst case). This gives a complexity of ( O(XY) ).

Overall time complexity for the Techie Approach: Considering that maintaining the sorted sets might be a one-time or infrequent operation, the most significant ongoing complexity is the selection of top products, which is ( O(XY) ).

While I could have implemented my own sorted set, I discovered a well-crafted package called sortedset. Why build from scratch when someone has already done the heavy lifting? (Why reinvent the wheel?).

package main

import (

"fmt"

"sort"

"github.com/wangjia184/sortedset"

)

// Iterator is used to traverse through a sorted set in descending order.

type Iterator struct {

set *sortedset.SortedSet // The sorted set to iterate over.

index int // The current position in the sorted set (based on rank).

}

// NewIterator creates a new iterator for the given sorted set, starting from the end (highest rank).

func NewIterator(set *sortedset.SortedSet) *Iterator {

return &Iterator{set, set.GetCount()}

}

// Next returns the next node in the sorted set based on descending rank. If there are no more nodes, it returns nil.

func (it *Iterator) Next() *sortedset.SortedSetNode {

if it.index >= 1 {

node := it.set.GetByRank(it.index, false) // Fetch the node by its rank.

it.index-- // Decrement the rank to move to the next node in the subsequent call.

return node

}

return nil

}

// getTopX retrieves the top X nodes across multiple sorted sets.

// It uses multiple iterators (one per set) to efficiently fetch the highest-ranked nodes.

func getTopX(its []*Iterator, x int) []*sortedset.SortedSetNode {

// result will hold the top X nodes across all sets.

result := make([]*sortedset.SortedSetNode, 0, x)

// nodes will temporarily hold the highest-ranked node from each iterator.

nodes := make([]*sortedset.SortedSetNode, len(its))

// Initialize nodes with the highest-ranked node from each iterator.

for i := range its {

nodes[i] = its[i].Next()

}

// Continue until we've fetched X nodes or exhausted all iterators.

for len(result) < x {

maxNode := (*sortedset.SortedSetNode)(nil) // Holds the current highest-ranked node across all iterators.

maxItIndex := -1 // Index of the iterator that produced maxNode.

// Loop through nodes to find the highest-ranked node.

for i, node := range nodes {

if node != nil && (maxNode == nil || node.Score() > maxNode.Score()) {

maxNode = node

maxItIndex = i

}

}

// If no nodes remain, break out of the loop.

if maxNode == nil {

break

}

// Add the highest-ranked node to the result.

result = append(result, maxNode)

// Replace the highest-ranked node in nodes with the next highest-ranked node from the same iterator.

nodes[maxItIndex] = its[maxItIndex].Next()

}

return result

}

Now let's check the above functions by Invoking them.

func convertToSortedSets(productSlices [][]Product) []*sortedset.SortedSet {

sets := make([]*sortedset.SortedSet, len(productSlices))

for i, products := range productSlices {

set := sortedset.New()

for _, product := range products {

set.AddOrUpdate(product.SKU, sortedset.SCORE(product.Score), nil)

}

sets[i] = set

}

return sets

}

func main() {

productSlices := [][]Product{

{

{"sku1", 5},

{"sku2", 3},

{"sku3", 1},

},

{

{"sku4", 8},

{"sku5", 6},

{"sku6", 7},

},

{

{"sku7", 9},

{"sku8", 11},

{"sku9", 10},

},

}

fmt.Printf("For lazy approach\n")

topProducts := mergeAndSortProducts(productSlices, 3)

for _, product := range topProducts {

fmt.Printf("SKU: %s, Score: %d\n", product.SKU, product.Score)

}

sets := convertToSortedSets(productSlices)

its := make([]*Iterator, len(sets))

for i, set := range sets {

its[i] = NewIterator(set)

}

fmt.Println("--------------------------------------------------")

fmt.Printf("For techie approach\n")

topX := getTopX(its, 3)

for _, node := range topX {

fmt.Printf("Value: %s, Score: %d\n", node.Key(), node.Score())

}

}

The output of the above code would be the same for both approaches i.e

For lazy approach

SKU: sku8, Score: 11

SKU: sku9, Score: 10

SKU: sku7, Score: 9

--------------------------------------------------

For techie approach

Value: sku8, Score: 11

Value: sku9, Score: 10

Value: sku7, Score: 9

In summary:

Lazy Approach: ( O(YZ log(YZ)) )

Techie Approach: ( O(XY) ) for selection, but also consider ( O(YZ log Z) ) for initial setup or updates.

Given these complexities, the techie approach is generally faster for selecting the top X products, especially when X is much smaller than ( YZ ). However, the actual performance can also depend on the constants hidden by the Big O notation and specific use-case details.

Since Z can be quite large compared to Y, the second option is blazing fast. I bet you can guess which one I chose. 😎

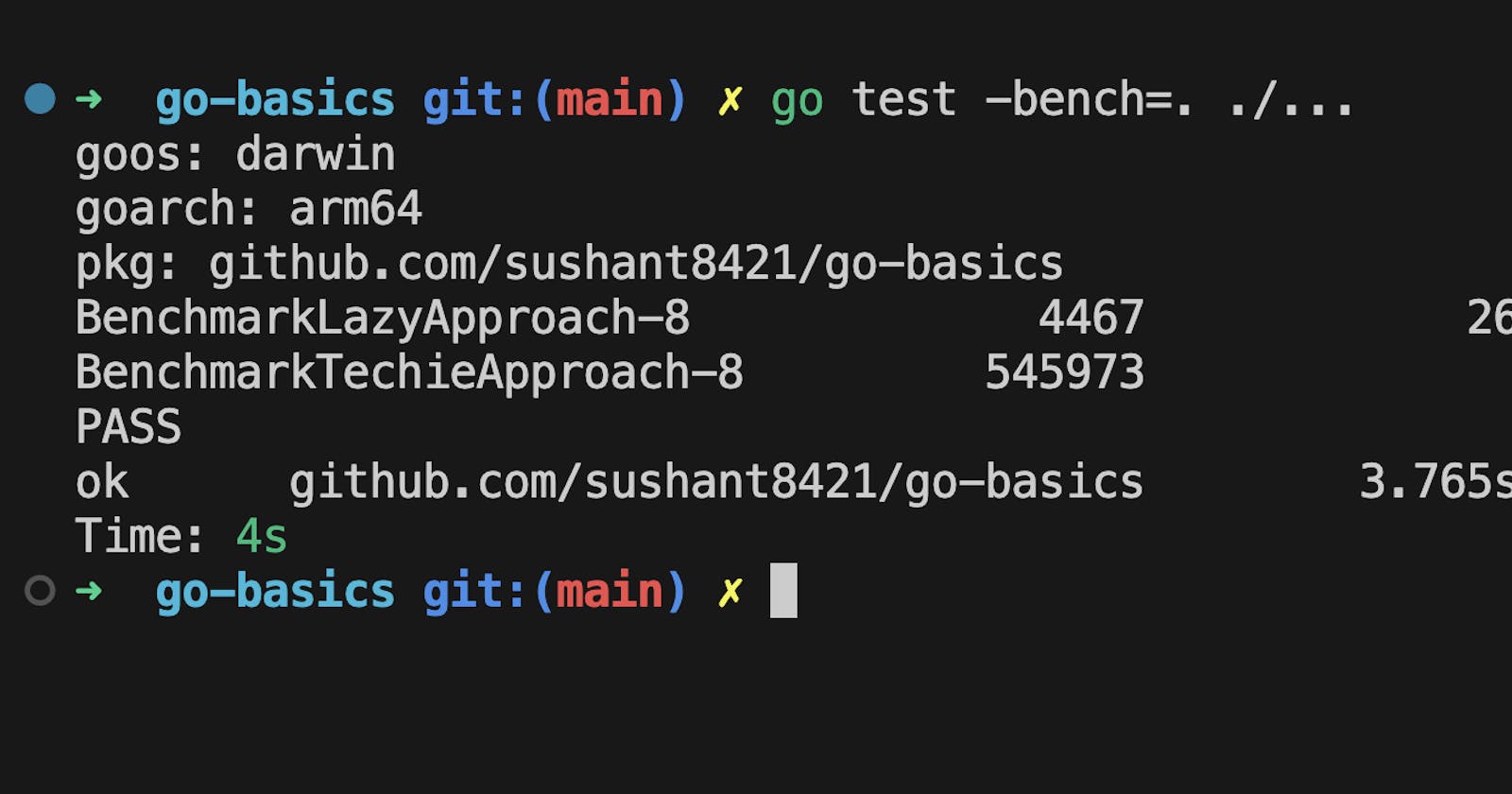

Rather than talking about it, let's measure it using some benchmarks

Benchmarking

But what's a solution without proof, right? So, I put both methods to the test and shouted, "Let the Games Begin!"

package main

import (

"math/rand"

"strconv"

"testing"

"time"

)

// we will be having some dummy products data for

// benchmarking on some real numbers

func populateProducts(sliceCount, sliceSize, maxScore int) [][]Product {

r := rand.New(rand.NewSource(time.Now().UnixNano()))

productSlices := make([][]Product, sliceCount)

for i := 0; i < sliceCount; i++ {

slice := make([]Product, sliceSize)

for j := 0; j < sliceSize; j++ {

sku := "slice" + strconv.Itoa(i+1) + "-sku" + strconv.Itoa(j+1)

score := int64(r.Intn(maxScore) + 1)

slice[j] = Product{SKU: sku, Score: score}

}

productSlices[i] = slice

}

return productSlices

}

// X = 10, Y = 20, Z = 150

func BenchmarkLazyApproach(b *testing.B) {

// Initialize product slices here...

productSlices := populateProducts(20, 150, 500)

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

mergeAndSortProducts(productSlices, 10)

}

}

func BenchmarkTechieApproach(b *testing.B) {

// Initialize sets here...

productSlices := populateProducts(20, 150, 500)

sets := convertToSortedSets(productSlices)

b.ResetTimer()

for i := 0; i < b.N; i++ {

its := make([]*Iterator, len(sets))

for j, set := range sets {

its[j] = NewIterator(set)

}

getTopX(its, 10)

}

}

Here's how they fared:

goos: darwin

goarch: arm64

pkg: github.com/sushant8421/go-basics

BenchmarkLazyApproach-8 4515 262250 ns/op

BenchmarkTechieApproach-8 588006 1999 ns/op

PASS

ok github.com/sushant8421/go-basics 3.442s

Here's a brief breakdown of the output from the Go benchmarks:

goos: darwin

- This indicates the operating system the benchmarks were run on. In this case, it's

darwin, which is the OS for Macs.

- This indicates the operating system the benchmarks were run on. In this case, it's

goarch: arm64

- This is the architecture of the machine's processor.

arm64is a 64-bit ARM architecture, commonly used in newer Apple M1 Macs.

- This is the architecture of the machine's processor.

pkg: github.com/sushant8421/go-basics

- This specifies the package for which the benchmarks were executed.

BenchmarkLazyApproach-8

This line provides the result for the benchmark of the

LazyApproachfunction.4515 is the number of iterations the benchmark ran in the

LazyApproachfunction.262250 ns/op indicates that, on average, the

LazyApproachfunction took 262,250 nanoseconds (or 0.262250 milliseconds) to complete a single operation.

BenchmarkTechieApproach-8

This line provides the result for the benchmark of the

TechieApproachfunction.588006 is the number of iterations the benchmark ran in the

TechieApproachfunction.1999 ns/op shows that, on average, the

TechieApproachfunction took 1,999 nanoseconds (or 0.001999 milliseconds) to complete a single operation.

PASS

- This indicates that all benchmarks were executed successfully without any errors.

ok github.com/sushant8421/go-basics 3.442s

- This shows the package being benchmarked and the total time taken to run all benchmarks for that package, which in this case is 3.442 seconds.

Inference: From the given results, the TechieApproach is significantly faster than the LazyApproach. On average, the TechieApproach takes just around 0.002 milliseconds per operation, while the LazyApproach takes approximately 0.262 milliseconds per operation.

But there's more. Some widgets/CMS items feature niche products, either combo products or Price stores, layered atop the existing categories. To resolve this, I employed the values field in the sorted set:

So the sorted set has three fields now

Key -> category

Score -> popularity score

Value -> productInfo like skuId, price, isCombo

So further filters could be added to the code to fetch top X products from required categories which are combos and are from a particular price range. The code part for that can be found here

TL;DR: The Takeaway

If your e-commerce platform has a similar widget-based structure for showing products from various categories, and if you're dealing with a high volume of products (Z >> Y), the sorted set and iterator approach is your knight in shining armor.

So there you have it, folks! This is how we hacked our way through categories and widgets, all to make sure you see that leather jacket you never knew you needed until now.

Remember, there's always a smarter way to solve a problem—you just have to look for it.